It’s not because I am lubricious; I am religiously inclined

Despite the definite article of the title, this non-album track – first released on EMI’s posthumous Jake in a Box collection, and thus a late addition to the Thackray canon – doesn’t follow other pen portraits (‘The Kirkstall Road Girl‘; ‘The Hair of the Widow of Bridlington’) in describing one woman in particular. Instead, women in the song — as in the deeply ambiguous ‘Miss World‘ — are largely interchangeable: ‘any old vicar’s missus will do.’ Unlike that topical piece, however, male lechery is not the prime target of the comedy. The singer repeatedly stresses there is no sexual implication (‘One little peck, nothing improper’) to his desires, even as the threatening tone of ‘one within my clutches’ leads logically to the ensuing physical violence. As such, the song functions not as a character study not of the wife of a vicar, but of the kind of man who pursues an unusual predilection, with little apparent respect for female agency.

Sympathy for the figure comes across in the first-person telling, the delusive rationalisations (‘It’s not a thing I’d do again). As in my previous post, on ‘I Stayed Off Work Today‘, Jake pits a somewhat naive character in the grip of an erotic obsession (‘I can’t get it from my mind’) against the full force of judicial authority. Jake’s version of the violent ‘Isabella‘ marks the limits of the obsessive theme; among others, ‘The Brigadier‘ explores the exercise of petty power. Here, however, it would be hard to argue for the subject’s innocence, despite his plaintive – plaintiff, even – appeal.

The singer has been building a ‘collection’ of apparently chaste encounters with the spouses of men from ‘most professions’ (Jake commonly defines people in shorthand by their professional roles). ‘Grocers’ are anomalous – largely, the men targeted for this campaign of cuckolding serve as functionaries of the state or of the institutions of financial control: tax inspectors, rent collectors, sergeants, inspectors. There is therefore an element of class war enacted upon the female body. Though the character pleads that he would never deliberately damage the vicar’s ‘property’ (perhaps the greatest threat to a male participant in a capitalist social system), the ‘collection’ reference makes clear that these kisses are imagined as a form of theft, a demonstration of oneupmanship. Nameless female figures are similarly co-opted as collateral for an attack on wealthy men, in response to economic envy, in many of the songs of Thackray fan Jarvis Cocker:

You see you should take me seriously

Very seriously indeed

‘Cos I’ve been sleeping with your wife for the past sixteen weeks

Smoking your cigarettes

Drinking your brandy

Messing up the bed you chose together

And in all that time

I just wanted you to come home unexpectedly one afternoon

And catch us at it in the front roomYou see I spy for a living

and I specialise in revenge

On taking the things I know will cause you pain(I Spy)

The particularly sexual threat present in the above is nonetheless mostly absent from ‘The Vicar’s Missus’, whose singer maintains at least a facade of innocence under the cloak of being ‘religiously inclined’. Framing the desire for a kiss as a pursuit of ‘Holy Mother Church’ might suggest an impulse towards desecration. This would seem to underlie the curious treatment of the ‘bishop’s consort’ – elsewhere, Thackray frequently makes no moral distinction between marital and pre-marital sex, but the ’embrace’ described here is dismissed as irrelevant for not being extra-marital. If what is really desired is the sin of adultery, then this feels like either an attack on clerical institutions, or a willed act of self-damnation.

Again, Jake’s Catholicism complicates matters. ‘Holy Mother Church’ seems to be a markedly Roman formulation; Catholic priests, like the Jesuits by whom he was educated, do not marry. Furthermore, ‘all such vicars and their ladies’, in an astonishingly broad statement, are described as ending up in Hell: the Anglican Communion has its problems, but it’s rare for Jake Thackray to summon the rhetoric of the Spanish Inquisition. ‘Hell or Hades’, however, implies a fundamental uncertainty about what religious system is governing the moral universe of this song. The simplest response, perhaps, would be to see the character’s quest as an expression of essential fallenness: in his dogged attachment to earthly love, albeit in a very niche form, the singer will find ‘the answer to [his] prayer’ in an inevitable damnation from which not even the servants of God will escape. That’s pretty strong stuff!

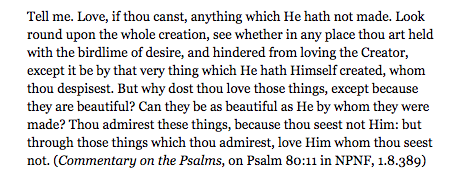

The theologian St Augustine does chastise mankind for the improper ordering of love, for fixing ‘our love on the creature, instead of on thee, the Creator.’ In being ‘religiously inclined’, the singer might perhaps claim to be loving earthly beauty (though physical attraction is not even mentioned) as a conduit to the divine:

But that’s the most charitable sense I can make out of it, and wouldn’t account for why everyone in the song is condemned to the fiery furnace. Do you have any other theories – psychological or theological – about what’s driving this peculiar character? Or does he just want to kiss a vicar’s missus, after all?

Playlist